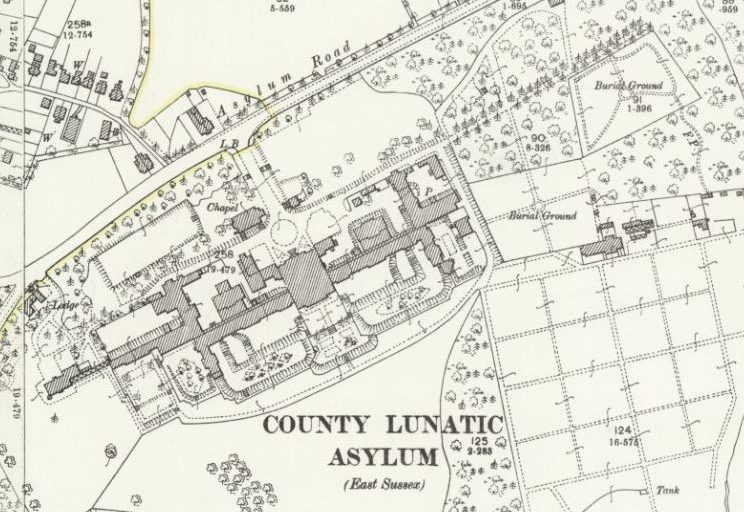

Sussex County Lunatic Asylum, Haywards Heath

(latterly named St. Francis Hospital)

When St Francis Hospital opened in 1859 it was then known as the Sussex Lunatic Asylum. Its first medical superintendent was Charles Lockhart Robertson, a largely forgotten figure now, but he was one of the most progressive asylum administrators of his day. He implemented a whole range of treatments from “pet therapy” to “Roman baths”. However, the main therapy was the institution itself with plenty of fresh air, productive work, a good diet and healthy exercise. In the summer, large numbers of patients regularly walked the six miles to Ditchling Common where mammoth picnics were held. Patients worked on the farm and after a couple of years the Asylum was self-sufficient in meat production. It was said that only tea and sugar were not produced there. All the furniture on the wards was also made by the patients. Under Robertson’s leadership, the Asylum soon became one of the most famous in Europe, regularly visited by curious foreign dignitaries who came to study its success. When he was away, Henry Maudsley – the founder of the Maudsley Hospital in London – would often come down and act as his locum.

Roberston lasted just over ten years at the Sussex Lunatic Asylum. Built for roughly 400 patients it soon became grossly overcrowded. This sabotaged its cure rate and, as other asylums eventually found out, became a dumping ground for those society didn’t wish to have in their midst. But as one of Roberston’s successors, Dr Saunders, once remarked, for a brief period “ Robertson, both by example and precept showed what could be done by the humane treatment of the insane…and did much towards breaking down prejudices and raised the asylum life to a higher level”.

Originally, the Asylum was built for “pauper lunatics” from all over Sussex. In 1897, in an attempt to ease the overcrowding, patients from the west of the county were transferred to a new hospital, Graylingwell, just to the north of Chichester. And in 1903, patients from the east of the county, were transferred to Hellingly, near Eastbourne. This last change left Brighton Borough Council in charge of the Asylum. And it was under this management that, for financial reasons, private patients were encouraged to come, sometimes at the expense of pauper lunatics from Brighton who were sent to other asylums outside the county.

During the First World War, life in the Asylum became even grimmer with staff shortages, war time rationing and patients being buried under its paths. In 1923, George Harper-Smith, was appointed superintendent and threw himself into counter-balancing the grim life of an institution by improving its social life. In the 1930s the Christmas celebrations alone lasted from almost the beginning of December to the middle of January, including what the local paper described as “the largest New Year Party in Mid-Sussex”. Best decorated ward competitions were regularly held and there were frequent money-raising events such as fetes and fancy-dress balls. Unfortunately, World War Two put a stop to almost all these activities.

Patients again lost weight due to war time rationing during the Second World War and their main activity was looking for firewood, working in the gardens or on the farm. Staff shortages became critical and one Christmas all the domestic staff refused to come in. But the war also brought about “advances” in treatment such as the use of ECT (Electro-convulsive therapy), brain operations, prolonged drug use and the employment of an educational psychologist. In fact, the hospital was the first one in England to have an ECT machine which they imported from America during the war.

Historic postcard of the asylum

On 5th July 1948, the hospital, now called the Brighton Borough Mental Hospital, was placed under the control of the NHS and was renamed St Francis, the name given to its chapel in November 1941. It was now to be run by the Regional Hospital Board. The NHS was inheriting, in many ways, a run-down hospital but with a neurological centre – Hurstwood Park – originally built as an admission hospital, which had established a national reputation for its excellence.

The change of management had little immediate impact on the hospital’s problems although there was greater public interest now that the general community, and not just Brighton, owned it. The age range of patients was wide, from 80 to just under two years old in 1948 and an increasing number of them were confined to their beds. Living conditions were harsh. Some patients received no drinks between 5.30pm and breakfast at 7.45am the next day. (Supper was only provided for those who stayed up after 7.30pm). And although there was a system of rewards – money and tobacco – for male patients who worked; there was none for the females.

The changeover did radically reduce the number of private patients from about 100 to 10 just under a year later, but overcrowding and staff shortages were still much in evidence. For these reasons, nurses still worked a 54-hour week and placing difficult patients in seclusion was common. The most significant development was the dramatic increase in the number of yearly admissions and discharges. In 1948 alone, there were 600 admissions and 533 discharges. Under the NHS, St Francis had a 25% wider catchment area which now contained 270,000 people of whom 200,000 lived in Brighton and Hove: thus the rise in admissions. Sometimes patients would be re-admitted several times during the same year. The hospital’s main population increasingly became permanent, fixed and elderly.

The asylum chapel today

With the advent of the NHS, St Francis undoubtedly benefited from the extra funding and could take advantage of better research facilities. Of course, the hospital faced many difficulties ahead, but it did continue to be a place of refuge and a place where no one who requested treatment was ever turned away. In the late 1950s, when Enoch Powell was Minister of Health, a white paper was produced which advocated the phasing out of asylums and the treatment of patients in the community – community care. So, for the last thirty or so years of the hospital’s life its infrastructure was gradually run down. By the time it closed in 1995 there were only two wards open.

One of the persistent laments of the staff was that there was very little rehabilitation when it was open and that when it closed not enough thought and care had gone into how patients would cope in the community. I only worked at the hospital briefly in the 1970s but I can vouch for the genuine attempts of the staff to improve the lives of the patients whether it was organising fund-raising or fetes. When it closed, I wondered whether this positive spirit would transfer itself to community care. I think this is a question that is still being asked.

Written by James Gardner with photography by Liam Heatherson